In-Betweenness

The "both/and but also neither" of being mixed-race with Savala Nolan.

"The things that make up our identities—gender, race, class, taste, nationality, etc.—are all relational and relative, which is part of the beauty and the problem." - Savala Nolan

From Rebecca, The Noodler

The US multiracial population has increased by 276% over the past decade, with 1-in-10 Americans identifying as being more than one race. As a Multiracial person, raising a Multiracial child, I find the factors driving this data - including that mixed-race folks can now freely choose how we want to identify on official forms, rather than being forced to check a box that doesn’t align with our identity - encouraging and validating. But, the unique and nuanced experience of living in-between the margins of race, culture, and social strata cannot be summed up, understood, or articulated by statistics - for this we need stories. And what excites me most about this shift are the rich and textured stories flowing from our growing ranks, giving words and context to the feelings, emotions, and experiences singular to - and shared by - an expansive mixed-race population.

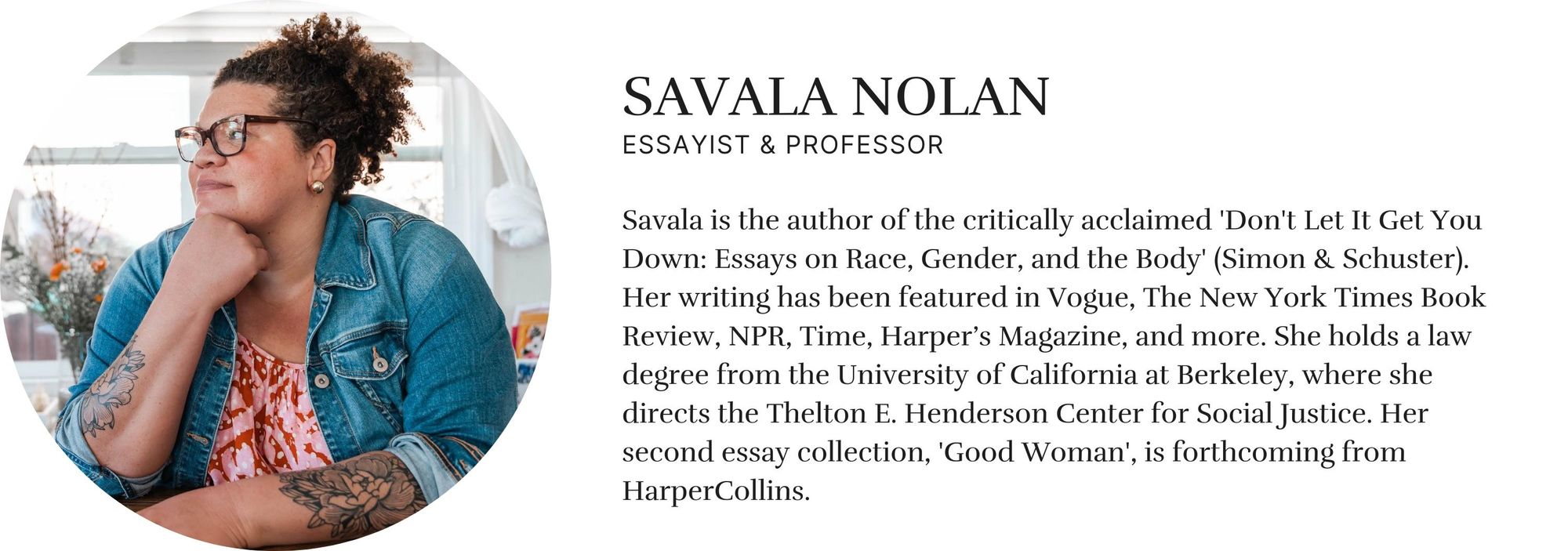

This week’s featured contributor, Savala Nolan, is one of the emerging resonate voices I am most excited about! Her bold and beautiful prose, exploring the liminality of being a mixed-race, multidimensional human, is a powerful, sobering, and validating revelation. The daughter of a White mother and a Mexican and Black father, Savala’s book, "Don’t Let It Get You Down: Essays On Race, Gender, and The Body," is a collection of essential essays unpacking the nuances of her existence as a liminal being and a life lived beyond the boxes of black and white, rich and poor, fat and thin. She shared her time with us to discuss her book (including her process for writing it), her thoughts on identity, bodily autonomy, navigating interracial friendships and family dynamics, living a well-examined life, and some of the hopes and dreams she has for her own mixed-race daughter.

Q&A

The Noodler: You have so poetically used liminality within your work to both claim and unpack the nuances of your identity - and the place mixed-race people hold in society. What initially drew you to liminality, and how did you develop your framework? Further, do you see living in liminality as positive/negative/neutral - or does it depend on the context?

Savala Nolan: Liminality chose me more than I chose it. I’m built of so many opposing identities and cultural spaces. I’m both Black and white (I identify as a Black or mixed Black woman). I’m descended from slave holders on my mom’s side and enslaved people on my dad’s side. I was exposed to profound generational poverty at times in my childhood but am the recipient of a private school (read: wealthy) education. I’ve been fat and thin many times since childhood and my body carries that. All of which is to say, for as long as I can remember, I’ve been in liminal, interstitial spaces—both/and but also neither. The choice I had was whether to fight or make peace with the dualities. Whether to choose a side, so to speak, or imagine myself as more of a border-crosser, a holder of many passports, with the joys and trials that come with perennial dislocation, or multi-location, in our culture. Many people have areas in their lives where they feel they have to choose. And if that’s what they want to do, terrific, have at it. But if choosing feels inauthentic, then I say get comfortable in the capacious space of the liminal and embrace what it has to offer.

TN: The truth-telling in your book, Don’t Let It Get You Down, is candid and raw. What was your process for examining and writing about your experience and then contextualizing them within a larger body of work?

SN: I’ll answer this two ways. In terms of my process as an essayist, I’m a naturally inquisitive person, so turning the gaze inward comes naturally. What makes an essay great for me as a reader, though, is the author’s ability to slam together the personal and the non-personal, creating something fresh and evocative. Without that collision of the internal and the external, you’re just reading a journal entry. One of my favorite writers, Elizabeth Hardwick, observes that the writer always precedes the material. In other words, you’re always going to have some of the author inextricably woven through the pages. But it can’t just be that. The essay has to gaze outward and inward at once, I think. It’s a dance I’m still learning and practicing.

In terms of actual craft, the editor of my first book, Dawn Davis, stated early and often that, in a collection, every single piece has to be nailed to the central thesis. Otherwise it’s a grab bag of random bits. If you want the whole thing to cohere, the essays must be spokes on the same wheel. Easier said than done!

TN: Identity is shaped in part by the relationships we have with our parents (that we have connections to), peers, and cultural/societal inputs. At what point does “identity” belong to you (ourselves) and no one else? Or is that not possible within the current systems that shape our society (not to mention, the nature of the individual psyche)?

SN: I’m not sure we should strive to own our identities separate and apart from others. I think the Nguni Banto term ubuntu, which is usually translated as “I am because we are,” has a pretty unassailable logic to it. The things that make up our identities—gender, race, class, taste, nationality, etc.—are all relational and relative, which is part of the beauty and the problem. So rather than aim to “own” my identity separate and apart from others, I’m more interested in exploring my identity in relation to others.

That said, there’s unquestionable value, especially for people who hold marginalized identities, in finding or creating an innermost room where your sense of self is not in conversation with the forces that marginalize you. For people who are poor, or trans, or fat, or Black, etc., fostering a register of your being and a layer of your life experience where who you are is solely yours, without considering yourself in relation to rich people or cis people or skinny people or non-Black people, etc., is therapeutic, generative, refreshing, and necessary.

It’s also been important work because the time, money, energy, and spiritual work I put into shrinking and controlling my body for the better part of forty years I can now put into modeling freedom.

TN: You describe feeling the “in-betweenness” of your body - while holding an appreciation for the work a body does within our political and cultural systems. How has this deep understanding and connection to your own body shaping the way you are (or want to) talk to your daughter about her body awareness?

SN: The most important thing for me to teach my daughter is this: her body is hers, fully and completely, and anyone or anything that infringes upon the free exercise of that sovereignty is inherently suspect. Be that a diet, a date, or a law.

It would not be possible for me to articulate this to her, or model it, if I were still dieting. The single most important work I’ve done as a parent is to divest from diet culture, work to cure my miseducation around fatness, and cherish myself as a fat woman. It’s been important work because it’s addressed some of my childhood (and teenage and adult) wounds, which of course makes me a more present and less reactive mom, even if only once in a while (all things are a work in progress).

It’s also been important work because the time, money, energy, and spiritual work I put into shrinking and controlling my body for the better part of forty years I can now put into modeling freedom. I don’t do it perfectly, or with unfettered ease. I make mistakes and at times struggle. Such is parenthood. Nevertheless, anything I can do to bolster and buttress her foundation as a person in a body that needs no changing, fixing, or controlling, and that seeks no approval, is worth doing.

I hope as we see increasing numbers of mixed kids we also see increasing numbers of non-mixed parents, particularly white parents, engaged in the tough but also joyful work of building a high capacity for intelligent, nuanced conversations about race, and a high capacity for making conscious, repeated choices that undermine racial hierarchy.

TN: How do you see the climate shifting for mixed-race children/adolescents and families? How are children’s experiences different now than from your childhood? What remains in the way of progress?

SN: Real talk: The biggest barrier to progress on nearly every bit of racial equity is white people who refuse to educate themselves fully on how our system of racial hierarchy was built, benefits them, and continually reproduces itself. The more bravely, deeply, and experientially that learning takes place, the more progress we make.

I was very lucky to have a white mother with a robust political consciousness around racial hierarchy. Was it perfect? Absolutely not. But it was there. And it mattered to me as a mixed child. It enabled me to be seen by her in my rich, nuanced, powerful Blackness, and it enabled both of us to critically examine her whiteness—again not always perfectly, but we can’t require perfection from one another. I hope as we see increasing numbers of mixed kids we also see increasing numbers of non-mixed parents, particularly white parents, engaged in the tough but also joyful work of building a high capacity for intelligent, nuanced conversations about race, and a high capacity for making conscious, repeated choices that undermine racial hierarchy.

TN: You’ve written about how when you were working in corporate law, that you felt like you had “failed” at meeting your father’s expectation that you would “make people whole” through your work as a lawyer. Has your sentiment changed? And have you considered how much you are helping to make people whole through your work as a writer?

SN: What a generous question! Goodness, I sure hope my dad is proud of me, wherever and whatever he may be now that he’s passed away.

I’m actually more convinced than ever that to stay in corporate law would have been an absolute disaster for me. My soul would have withered over the years. For a creative person with my heart on my sleeve and a perpetual preference for the underdog, corporate law was at such odds with my values that to keep doing it would have been a massive mistake.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t good people who thrive doing corporate defense for their whole career – life is complex and people have their own journeys. I do question, though, anyone doing that work and enjoying the salary without making significant contributions to social justice issues that, at a minimum, offset what it means to serve the most powerful in society.

As for writing, I sometimes get a note or DM from someone who says that something I wrote helped them articulate a feeling they’ve long had but never been able to put their finger on, or gave them a glimpse of a kind of freedom they want, and it is the most unexpected and fulfilling thing. If what I write helps anyone be whole, all I can say is thank you.

For most people of color, race is a huge part of our identity and we know it. For most white people, race is a huge part of their identity and they don’t know it.

TN: We can’t help but think about how much better off we’d be as a society if every person had the same will, curiosity, concern, and bravery to examine this country’s racial history - and their personal family histories - in the way you have. After doing more than your fair share of the hard work, what advice do you have for someone who might be afraid or ambivalent about what they might find? Why is it critical for all of us to do the work if we want to move forward and through this - as a country - and have any hope at racial reconciliation?

SN: I’d say, do it anyway! When it comes to rectifying and disrupting racial dominance, and to investing in a more morally honest version of equality, fear is a poor excuse for inaction.

Examine the fear closely. Is it truly paralytic to consider that, for instance, someone in your family line enslaved people? Or is the paralysis rooted in having to face that you might be someone who learns that and does nothing with the information. Is the paralysis rooted in having to look in the mirror at your actions, not theirs. I think in many cases it is. All the more reason to be afraid, and do it anyway! If for no other reason than to live a well-examined life, and to know yourself more deeply, do it anyway.

As to why it’s important, well, if we’re not honest in locating the problem we can’t reach it with our solutions, our secrets keep us sick, and transformation is most possible among people who see themselves or each other accurately.

TN: In your essay, “Dear White Sister”, you write, “If interracial friendships are going to be fully authentic and safe, they have to deal with race.” Can you expand upon this statement - particularly for those who have yet to read your work?

SN: For most people of color, race is a huge part of our identity and we know it. For most white people, race is a huge part of their identity and they don’t know it. This alone is a recipe for discord. And the discord will often be born by the person of color because, again, they have been required by life to develop a sensibility and skillset around race that white people are generally not required to develop. Over time, it’s like the person of color is carrying a backpack in the friendship, and every microaggression or flagrant aggression or blindspot or casual moment of privilege is a rock going into that backpack. Eventually, the bag is full and heavy and awkward. And the white friend is either under the illusion that rocks are weightless (“I don’t see color” or “My family isn’t racist”) or that there’s nothing they can do to help (“I don’t know how to address racism” or “I’m afraid” or “I’m triggered and can’t keep going”). Resentment and fatigue build, and things fall apart. This is what I most commonly see, and what I’ve experienced. It doesn’t have to be this way, but it often is.

The white friends I’m closest too are the ones I can be most honest with about race, but I don’t have a single white friend with whom I am fully honest all the time. I would guess that’s true for nearly every person of color in an interracial friendship. Every single white friend I have, I sometimes keep my mouth shut. Is this situation a dealbreaker? No, because I’ve decided that, in my most important, cherished, wonderful relationships with white people, “zero-tolerance” on race issues can’t be the standard. We’re all human, we all do things that are less than totally optimal or maximally conscious. At this point in my life, the question is: is the overall bond worth a certain amount of race-related discord from time to time? Again, perfection is not a real-world standard. I may well have gay friends, for example, who bite their tongue when, despite my best intentions, I display some sort of bias or lack of awareness. Do I respect their right to bring it up with me, or not? Absolutely. Would I want grace from them either way? I would. You find what works for you given the entire picture of the relationship.

Our bodies meld and cohere and disrupt “race” in ways that point out how silly the notion of separate racial categories is on a biological and scientific level.

TN: There are an increasing number of influential voices sharing their unique stories and perspectives and influencing cultural and societal understandings of the mixed and multi-racial experience. What kinds of stories and discourse do you hope to see more of?

SN: Mixed people as a cohort call society to increase the sophistication of its conversations around race. Most powerfully, I think, we ask society to hold the fundamental paradox of race, which is that it’s both a made-up social construct and an incredibly important, rich, impactful part of life. Our bodies meld and cohere and disrupt “race” in ways that point out how silly the notion of separate racial categories is on a biological and scientific level. Yet our bodies also meld and cohere and disrupt racial categories in ways that show us just how tightly we cling to them, and how real they are on a sociological and emotional level. What an incredible and generative tension! What a potential site for individual and communal knowledge. You don’t have to be mixed to learn from the mixed experience.

TN: We can’t wait to read more of your writing. Can you tell us anything about the new book or other projects that you’re working on that we can support?

SN: My next book is called Good Woman (TBD 2024). It’s a collection of essays that grapple with the idea of being a “good woman,” interrogating issues of power, race, the body, history, social theory, law, and art, and bringing the personal, political and cultural elements of womanhood into conversation. I also write two micro-essays for Medium each month, and I post a lot of musings on Instagram, mostly related to race and/or diet culture. I love chatting with readers so reach out!